I have had fiction and nonfiction published in many literary magazines: Triquarterly, Glimmer Train Stories, North American Review, Colorado Review, Creative Nonfiction, Fourth Genre, Another Chicago Magazine, killingthebuddha.com, Lost, the Chicago Reader, and others. Awards include an Illinois Arts Council Fellowship in prose and an Illinois Arts Council literary award for creative nonfiction. I have received prizes in Chicago Public Radio’s Stories on Stage competition, Chicago’s Guild Complex Prose series, Glimmer Train’s short fiction competitions, and the Jewish Cultural Writing Competition of the Center for Yiddish Culture. See Links to these sources.

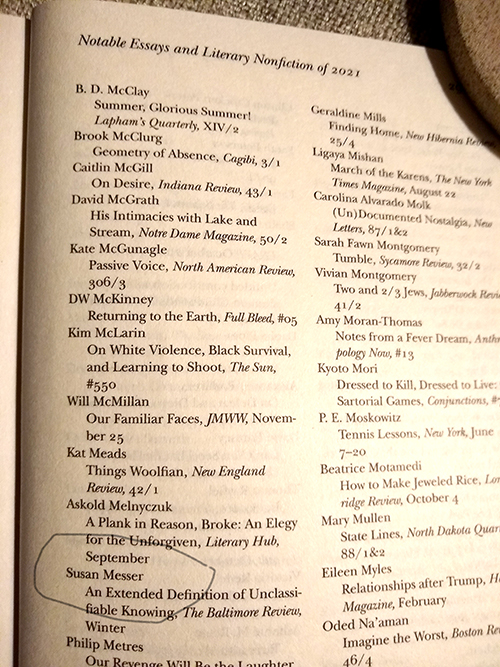

In 2022 my essay "An Extended Definiton of Unclassifiable Knowing" from Baltimore Review was included in Alexander Chee's The Best American Essays.

Below is a selection of excerpts from my work.

An Extended Definition of Unclassifiable Knowing

Baltimore Review

My deepening connection with another family based on confusion between our addresses.

When my husband and I bought our house, it had a clanky black metal mailbox screwed into the stucco near the front door, and we hadn’t lived there long when we found a letter in it for people with the last name Southwick. The people we bought the house from were named Elsass, so it wasn’t for them, and (at that point) we didn’t know anyone named Southwick, so I wrote NO SUCH ADDRESSEE on the envelope and put it back in the box.

Why Detroit?

Triquarterly

A review essay of two books about Detroit

When I told my aunt—a lifelong Detroiter—that my novel about her city had found a publisher, she said, “Just don’t use its name in the title. People don’t like to think about Detroit.”

It’s true that some don’t—in the same way some of us avoid thinking about the chronically ill. It’s painful to have no solutions, discomforting to realize that such afflictions could befall me as well, easier to look away and assume the sufferer feels shame about having a condition that never improves and never goes away.

On the Promenade Deck

Superstition Review

My homage to Thomas Mann's Magic Mountain.

Sleep comes easily in the wonderful chair with the fine blanket, the good air, and the gentle motion of the ship. Only sleep would explain the missed transition from open water to mountainous islands that now rise before her. The voice on the loudspeaker—Gordon, the social director—announces that they have entered Prince William Sound, the last great landmark before they dock in Seward tomorrow. They are in a narrow channel, with strings of islands not so very far from the side of the ship where she sits (Charles would have known if it was port or starboard). The mountains are covered with greenery—pine or spruce growing along rocky shore, then extending up, a velvet carpet. Heavy clouds rest along their ridges and poof into their valleys. She finds it cluttered. Compared to the forever expanse of open water, that is. On this journey, Julia’s companion has been the perfect fit of sea and sky at the horizon, stretching out, out, out… . She would have liked to slip through the thin line, like a piece of mail through a slot, like a sea otter in the water.

The air is cold, and damp, so she places her book and reading glasses on the wooden table and adjusts her blanket around her legs, pulls it up to her neck, tucks it around her shoulders and the whole length of her thin body. Julia’s chair is lacquered wood, padded the whole length by a thick navy cushion. An excellent chair. Her blanket is of checked wool—good quality; dry clean only. And it is the last day.

Dots on the Page

Creative Nonfiction

The roots of my life as an editor.

When I was just learning to read, I had a book about a brother and sister named Dick and Judy. Not Dick and Jane--I always say--but Dick and Judy. One night, I sat on the couch in my living room, attempting to read this book. I must have had the concept of words by then but not the concept of sentences, because this is more or less what I saw:

Here comes Dick Dick is a boy

Here comes Judy Dick is her brother

I read these words again and again, and they didn’t make sense. Why did the boy have the same first and last name? And why was Judy Dick someone’s brother? And the more I tried to understand—the repetitive names, the odd relationships--the more frustrated I became. I must have screamed or thrown the book across the room, because one of my parents came to the rescue and asked what was wrong.

“Why are these people called Dick Dick and Judy Dick?” I demanded. “None of this makes sense.”

The rescuing parent recognized the problem and explained punctuation: The little dots on the page are important. Each marks the end of a unit; when you see one, you pause, and then go on to the next idea, like this.

Here comes Dick. Dick is a boy.

Here comes Judy. Dick is her brother.

When I heard that, I got a warm, glowing sensation of understanding—that this tiny dot of ink could unlock meaning on the page.

Stone Age of Intimacy

North American Review

A portrait of a practical little Italian girl.

Arlene is a practical girl. I mean, she’s down to earth and she seems to understand all the things I don’t—everything from how to be the boss with your kids to pulling the starter on the lawn mower. And her husband’s a handyman, so through him, she knows a lot about how things work. Once, one of the light switches in my house started to melt and send out smoke. I was scared, had no idea what to do, so I called Arlene. All I had to say was, “Smoke... coming out of my light switch,” and she ran over to check it out. No questions asked. She made a bee line for my basement, flipped the circuit breaker, came up, removed the offending switch, and that was that.

She’s a nurse, too, so anytime a child on the block has a fever or falls off a bike and cuts their lip, Arlene’s the one to call. She’s got what I call comforting hands, and she always knows what to do—whether to use ice or heat (one of the things I can never remember), whether to go to the emergency room or just lay low. What a relief to have her there.

I guess she can be a real spit fire, too. You wouldn’t necessarily know that from talking to her, but I heard from her husband. One summer evening, a bunch of us neighbors were hanging around on the front lawn, just shooting the breeze. She was mad at her teenage son because he took the car when she’d said he couldn’t. And to let off steam, she was making fun of him, filling us in on his secrets. How he goes through the house, from one mirror to another, primping like a bird, checking his every angle, every hair, before he’ll step out the door. We’re all chuckling along with her in sympathy when the son pulls up. Arlene spots him and marches off to discuss the matter at hand. Meanwhile, Arlene’s husband watches after her, shakes his head, says in a whisper, a warning, “Never mess with a little Italian girl--if you know what’s good for you.” I never thought of her as a little Italian girl before, but there you are. She is a little thing, that’s for sure.

September Song

Glimmer Train Stories

Two sisters at the bedside of their dying father.

Two sisters stand in the dim light of a hospital room. They are tiny women—less than five feet tall, smaller than size-five shoe. The younger one, Renee, has a silver streak in her close-cropped black hair, and no jewelry, while the older one, Jeannine, wears cat-eye glasses, New York auburn hair, and complicated earrings.

A man, their father, lies in the bed, head on the white pillow. Closed eyes, wisps of white hair, bruised and punctured arms, so thin and weak. Lines and wires lead to tubes and dripping bottles; monitors display graphs and blinking lights. The hospital’s name is stamped on his thin gown in a repeating red-and-blue pattern: Providence, providence, providence, providence. His wrists are restrained, in soft terry-cloth bands near his waist.

“I hate the bands,” Renee says. She imagines the torture of having her own hands restrained. “Look at him. What damage could he do?”

“He bit through the ventilator,” Jeannine reminds. “Just yesterday.”

“But he’s still alive,” says Renee.

He opens his eyes, and when he sees that both his daughters are beside him, here from the West coast and the East, he gives them the mother of all eye rolls: taking in the full meaning of their presence. Had he not always been the one to fetch them at the airport--flight numbers and itineraries posted on the refrigerator for weeks in advance? He tugs at the wrist bands, his hands in a fist.

My World Cup Runneth Over

After Hours: A Journal of Chicago Writing and Art

Issue #39, Winter 2020

What I see through my window

My neighbors were having their house re-stuccoed, a job that was supposed to take eight days, but between the rainy ones and the blistering ones, the work went on and on.

The crew of men, like most crews of men who work around my neighborhood in the heat and the rain, spoke Spanish among themselves. They also brought the best lunches, tortillas warmed over little portable burners, wrapped around what looked like savory fillings. I collect these images from the window of my home office and on my midday walks that criss and cross this town.

One morning, the crew’s radio was playing, loud enough to distract me from my work, and my first impulse was to label it an imposition. But when I tuned into the urgency of the radio narration, punctuated by the collective elations and dejections, I knew it could only be one thing: a sports event. So, sitting at my desk, I googled to find out whether a world cup game was in progress. There was: Mexico vs. Sweden.

My thought process: The stucco crew spoke Spanish. The Stucco crew was listening to a world cup game between Mexico and Sweden. The stucco crew inflated and deflated in perfect synchronicity with the radio crowd. Ergo, the stucco crew was Mexican.

Not so fast. Perhaps the crew felt more affinity for Mexico than for Sweden—logical—but that didn’t mean they were from Mexico, or even that they were all from the same country. And then I began to wonder which countries they were from, and more pressing for them, what their immigration status was.

Page top

Page top